Barn Owl (Tyto alba)

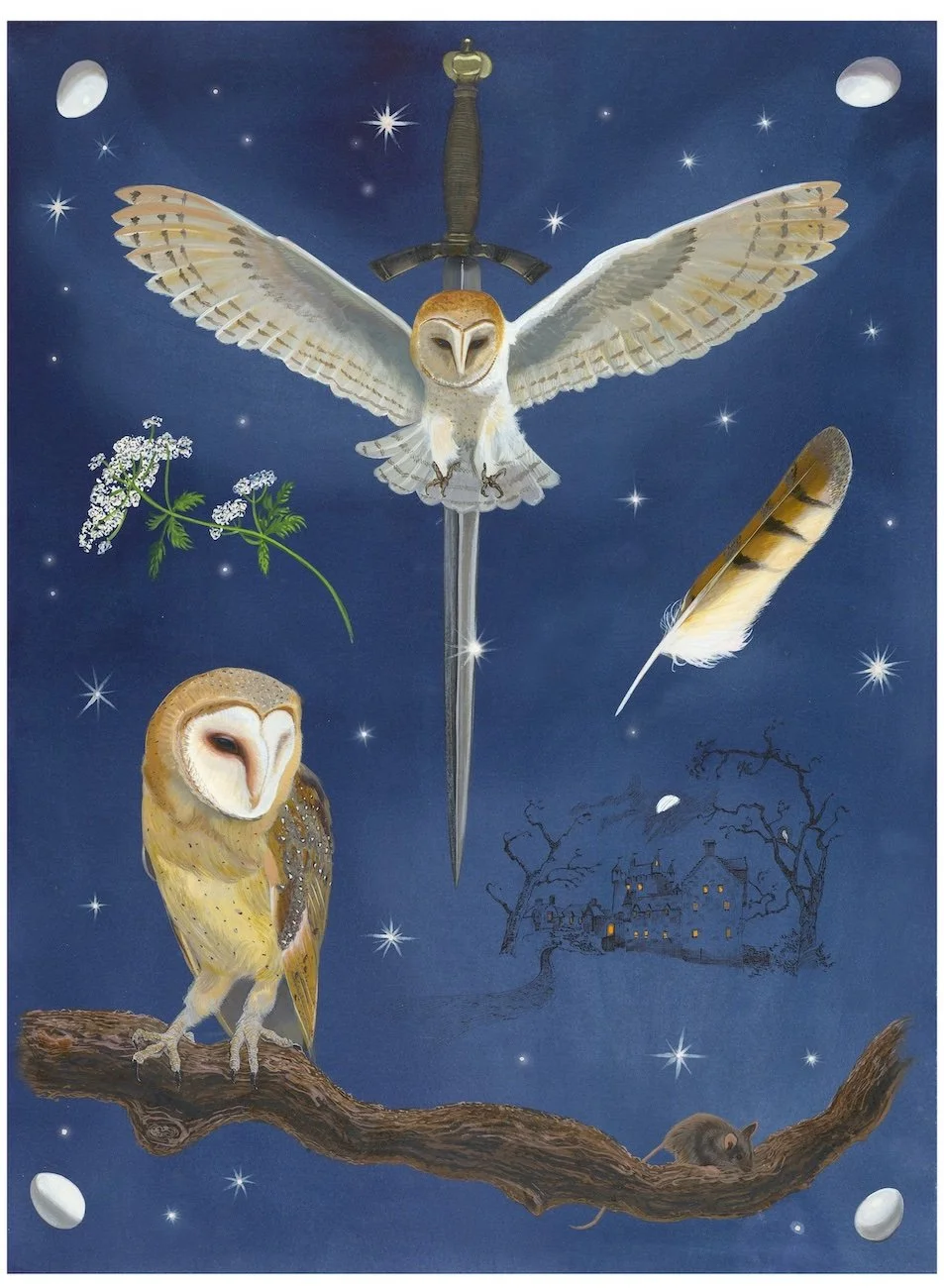

Barn Owl (Tyto alba) by Missy Dunaway, 30x22 inches, acrylic ink on paper

Painting Key

Fauna: 2 Barn owls (Tyto alba), 1 mouse

Flora: Hemlock, oak

Objects: 1 Dagger, 4 barn owl eggs, 1 barn owl feather, illustration of Cawdor Castle, stars

Shakespeare’s Barn Owl

Occurrences in text: 20

Plays: Cymbeline, Hamlet, Henry VI Part 1, Henry VI Part 3, King Lear, Love’s Labour’s Lost, Macbeth, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Titus Andronicus, Troilus and Cressida, The Two Noble Kinsmen

Name as it appears in the text: “owl”

It is a dark night at Cawdor Castle. Lady Macbeth stands alone in a dim room as lightning flashes through the nearby window, casting her figure amid the remnants of a celebration. The revelry has faded, and the same wine that lulled her guests to sleep has quickened her blood. She waits for a sign that her guest of honor, King Duncan, has been murdered by her husband. Then she hears it: the piercing cry of an owl, “the fatal bellman.”

Macbeth (Act II, Scene 2, Line 4)

LADY MACBETH: Hark!—Peace.

It was the owl that shrieked, the fatal bellman,

Which gives the stern’st good-night. He is about it.

The doors are open, and the surfeited grooms

Do mock their charge with snores. I have drugged

their possets,

That death and nature do contend about them

Whether they live or die.

The owl is an enduring symbol today, though for starkly different reasons than for Lady Macbeth’s. Once you start looking for them, you’ll see owls everywhere. They are printed on dinner plates, clothing, and children’s books. In Let’s Explore Diabetes with Owls, humorist David Sedaris muses, “Does there come a day in every man’s life when he looks around and says to himself, ‘I’ve got to weed out some of these owls’?”[1] As a fan of owls, I was eager to explore this species, which has fascinated people for as long as birds and humans have coexisted. Yet instead of the sweet, bespeckled owl I was accustomed to, I encountered an ominous predator in Shakespeare’s writing. For example, in the narrative poem, The Rape of Lucrece, the antagonist, Tarquin, is compared to an owl attacking the gentle, dove-like Lucrece. To make sense of this contrast, I had to widen my perspective and study owls in early modern culture.

Which Owl is Shakespeare’s Owl?

The word “owl” is Germanic, with its earliest recorded usage in Old English (before 1150), where it carried two meanings: the bird, or the downy wool of a sheep.[2] True to its name, the owl has a fluffy appearance that recalls soft wool. By contrast, most flight birds display a sleeker form with sharply-contoured feathers that create a shell-like covering to trap heat around the body. Owl feathers share this insulating quality, yet the edges of their feathers are uniquely soft and frayed, which muffle the sound of flight, enabling them to hunt in silence.[3]

William Shakespeare uses the word “owl” twenty times throughout his plays and poetry without ever naming a species. Initially, I planned to depict the tawny owl, the most common British owl, as a stand-in for them all.[4] But on closer reading, I noticed that he describes both screeching and hooting owls. This presented a problem because the tawny owl hoots but rarely will screech, while the barn owl, the most common screeching owl, cannot hoot.[5] Shakespeare must have envisioned at least these two distinct species while populating his theatrical landscape, which increased my project’s count from sixty-four to sixty-five species.

Today’s familiar owl, which lives in the Hundred Acre Wood and clutters David Sedaris’s home, is genial, studious, and wise. This persona is possibly rooted in the owl’s classical associations with Minerva, the goddess of wisdom in Roman mythology. Its human-like facial structure may also have encouraged this idea. The owl’s flat, circular facial disc, forward-facing eyes, and downward beak give it an oddly human quality, which may explain why we endowed it with human intelligence. This owl is typically depicted with brown plumage and a hooting call.

The Evil Prophet of the Night: The Barn Owl

When I searched for owls in the Folger Shakespeare Library’s archive, I found several depictions of small, brown owls, but far more illustrations of the barn owl—likely the same screech owl Lady Macbeth heard. The barn owl seems to have carried greater cultural weight in early modern England than the tawny owl, so I chose to paint and study Shakespeare’s barn owl first.

The barn owl is very recognizable because it is white and yellow with a heart-shaped face, dark slanted eyes, and an obscured beak. Although beautiful to modern eyes, Shakespeare’s audience thought the barn owl was grotesque, largely because of its unearthly call.[6] It produces a long-drawn-out shriek, and it can hiss like a snake. Many colloquial names around the British Isles, such as “roarer” (Borders), “hissing owl” and “screaming owl” (Yorkshire), are inspired by its voice.[6a]

Superstitions swirl around the barn owl throughout Europe. It may be the most feared and maligned bird I have encountered. Although Roman mythology venerates the owl, Greek mythology regards it as a symbol of misfortune.[7] Francesca Greenoak’s 1981 book, All The Birds of The Air, shares several fascinating beliefs about owls: It was a widespread custom to nail an owl to a barn door to avert the evil eye. It was also believed that eating owls’ eggs would endow a person with their keen eyesight. The Gaelic name for barn owl conjures an unsettling image of a witch: Cailleach-oidhche Gheal, meaning “white old woman of the night.” Witches were believed to depend on owls, and they were frequently used in charms and potions.[8] Back to Macbeth, the witches include an “owlets wing” in their brew.

Macbeth (Act IV, Scene 1, Line 12)

SECOND WITCH: Fillet of a fenny snake

In the cauldron boil and bake.

Eye of newt and toe of frog,

Wool of bat and tongue of dog,

Adder’s fork and blindworm’s sting,

Lizard’s leg and howlet’s wing,

For a charm of powerful trouble,

Like a hell-broth boil and bubble.

ALL: Double, double toil and trouble;

Fire burn, and cauldron bubble.

In the fateful scene where Lady Macbeth is awaiting news of King Duncan’s demise, she believes the owl’s scream is an announcement of death, a popular early modern interpretation.[9] However, there were more meanings that Lady Macbeth would have been wise to consider: perhaps the owl was urging the murderous couple to repent their sins, supported by a more sympathetic depiction of a barn owl in the twelfth-century poem, The Owl and the Nightingale.[10]

The Owl and the Nightingale, Line 863

OWL: Before they leave their earthly home

All men, as sinners, should atone

through crying, till the tears they weep

make bitter what they thought was sweet.

God knows I sing because I’m fair

& not to catch men in a snare.

My song of longing carries tones

of lamentations in its notes,

so man will know his crimes & grieve

his misdemeanours; he’ll believe

the song I’m singing, urging him

to own his guilt & mourn his sins.

Beyond Macbeth, the barn owl continues to mark tragedy in Shakespeare’s histories. In Henry VI Part 3, which chronicles England’s War of the Roses, we first encounter the Duke of Gloucester, who will later become the infamous Richard III. Despite his deformity, Richard demonstrates remarkable physical prowess on the battlefield, along with the ruthless cruelty that will define his reign. After Richard kills the king’s son, and moments before meeting his own death, King Henry laments, “The owl shrieked at thy birth,” casting the bird as an omen of evil and ill fortune.

Henry VI Part 3 (Act V, Scene 6, Line 35)

KING HENRY: Hadst thou been killed when first thou didst presume,

Thou hadst not lived to kill a son of mine.

And thus I prophesy: that many a thousand

Which now mistrust no parcel of my fear,

And many an old man’s sigh, and many a widow’s

And many an orphan’s water-standing eye,

Men for their sons, wives for their husbands,

Orphans for their parents’ timeless death,

Shall rue the hour that ever thou wast born.

The owl shrieked at thy birth, an evil sign;

The night-crow cried, aboding luckless time;

Dogs howled, and hideous tempest shook down trees;

The raven rooked her on the chimney’s top;

And chatt’ring pies in dismal discords sung;

Thy mother felt mjore than a mother’s pain,

And yet brought forth less than a mother’s hope:

To wit, an indigested and deformèd lump,

Not like the fruit of such a goodly tree.

Teeth hadst thou in thy head when thou wast born

To signify thou cam’st to bite the world.

And if the rest be true which I have heard,

Thou cam’st—

RICHARD: I’ll hear no more. Die, prophet, in thy speech;

Stabs him.

For this amongst the rest was I ordained.

The barn owl similarly appears in a heart-wrenching scene of King Lear. Lear is furious that his daughters, Regan and Goneril, insist he dismiss his knights or he will no longer be welcome in their homes. An argument ensues, and Lear is locked out of their castle. He evokes the owl just before he rushes out into the ill-fated storm, where he loses the last vestiges of his sanity and dignity:

King Lear (Act II, Scene 4, Line 239)

LEAR: Return to her? And fifty men dismissed?

No! Rather I abjure all roofs, and choose

To wage against the enmity o’ th’ air,

To be a comrade with the wolf and owl,

Necessity’s sharp pinch. Return with her?

Why the hot-blooded France, that dowerless took

Our youngest born—I could as well be brought

To knee his throne and, squire-like, pension beg

To keep base life afoot. Return with her?

Persuade me rather to be slave and sumpter

To this detested groom.

Behind The Painting

In my painting, I departed from my usual composition by toning the paper to reference the bird’s nocturnal world. I wanted to include a Shakespearean plant that shared the owl’s dark reputation, so I chose the poisonous hemlock; another ingredient in Macbeth’s witches’ brew. I drew inspiration from John Jellico’s 1889 illustration of Cawdor Castle, where King Duncan is murdered.

Left: Macbeth and Lady Macbeth entering Cawdor Castle in an illustration by John Jellicoe, 1889. Folger Shakespeare Library

Right: Cawdor Castle by Missy Dunaway

The owl’s flight is paired with Macbeth’s dagger. The dagger illustrated was owned by Sir Henry Irving and is now held in the collection of the Folger Shakespeare Library. Irving, one of the great Shakespearean actors of the nineteenth century, famously performed Macbeth, among other tragic figures.

Left: Sir Henry Irving (1838 - 1905) as Macbeth. Photograph by J. Speed. Folger Shakespeare Library

Right: A dagger owned by Sir Henry Irving. Folger Shakespeare Library

By tracing the owl through Shakespeare’s tragedies and histories, I came to understand it as more than a nocturnal bird; it is a harbinger, a witness, and a mirror of human fear and consequence. Its silence, flight, and cry all resonate with the tragedies it witnesses in Macbeth, King Lear, the Henry VI trilogy, The Rape of Lucrece, and more. Through this lens, the owl emerges as a bridge between the natural world and the human imagination, reminding us that even a small bird can carry weighty meaning.

Endnotes

[1] David Sedaris, Let’s Explore Diabetes with Owls (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2013).

[2] Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “owl,” accessed 20 October 2025, https://www.oed.com/dictionary/owl_n?tab=factsheet#32278747.

[3] Barn Owl Trust, “Barn Owl Hunting and Feeding,” Barn Owl Trust, accessed 20 October 2025, https://www.barnowltrust.org.uk/barn-owl-facts/barn-owl-hunting-feeding/.

[4] Carys Matthews, “British Owl Species: How to Identify, Diet and Where to See,” BBC Wildlife Magazine: Discover Wildlife, accessed 20 October 2025, https://www.discoverwildlife.com/animal-facts/birds/uk-owl-guide-how-to-identify-where-to-see.

[5] Barn Owl Trust, “Owl Identification – What Owl Was That?” Barn Owl Trust, accessed 20 October 2025, https://www.barnowltrust.org.uk/barn-owl-facts/uk-owl-species/.

[6] James Edmund Harting, The Birds of Shakespeare (London: John Van Voorst, Paternoster Row, 1871).

[6a] Francesca Greenoak, All the Birds of the Air. 2nd ed., (Penguin Books, 1981), p. 167.

[7] James Edmund Harting, The Birds of Shakespeare (London: John Van Voorst, Paternoster Row, 1871).

[8] Francesca Greenoak, All the Birds of the Air. 2nd ed., (Penguin Books, 1981), p. 167.

[9] James Edmund Harting, The Birds of Shakespeare (London: John Van Voorst, Paternoster Row, 1871).

[10] Simon Armitage. The Owl and the Nightingale (London: Faber & Faber Limited, 2021). p. 44.